当前位置:首页 → 职业资格 → 教师资格 → 中学英语学科知识与教学能力->Therearetwokindsofmotiveforeng

There are two kinds of motive for engaging in any activity: internal and instrumental. If a scientist conducts research because she wants to discover important facts about the world, that's an internal motive, since discovering facts is inherently related to the activity of research. If she conducts research because she wants to achieve scholarly renown, that's an instrumental motive, since the relation between fame and research is not so inherent. Often, people have both for doing things. What mix of motives--internal or instrumental or both--is most conducive to success? You might suppose that a scientist motivated by a desire to discover facts and by a desire to achieve renown will do better work than a scientist motivated by just one of those desires. Surely two motives are better than one. But as we and our colleagues argue in a paper newly published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, instrumental motives are not always an asset and can actually be counterproductive to success. We analyzed data drawn from 11320 cadets in nine entering classes at the United States Military Academy at West Point, all of whom rated how much each of a set of motives influenced their decision to attend the academy. The motives included things like a desire to get a good job later in life and a desire to be trained as a leader in the United States Army

How did the cadets fare years later? How did their progress relate to their original motives for attending West Point? We found, unsurprisingly, that the stronger their internal reasons were to attend West Point, the more likely cadets were to graduate and become commissioned officers. Also unsurprisingly, cadets with internal motives did better in the military (as evidenced by early promotion recommendations)than did those without internal motives and were also more likely to stay in the military after their five years of mandatory service. Remarkably, cadets with strong internal and strong instrumental motives for attending West Point performed worse on every measure than did those with strong internal motives but weak instrumental ones. They were less likely to graduate, less outstanding as military officers and less committed to staying in the military. Our study suggests that efforts should be made to structure activities so that instrumental consequences do not become motives. Helping people focus on the meaning and impact of their work, rather than on, say, the financial returns it will bring, may be the best way to improve not only the quality of their work but also their financial success. There is a temptation among educators and instructors to use whatever motivational tools are available to recruit participants or improve performance. If the desire for military excellence and service to country fails to attract all the recruits that the Army needs, then perhaps appeals to “money for collegecareer training” or “seeing the world”will do the job. While this strategy may lure more recruits, it may also yield worse soldiers. Similarly, for students uninterested in learning,financial incentives for good attendance or pizza parties for high performance may prompt them to participate, but it may result in less well-educated students.

According to the passage, which of the following is conducive to career success?

细节题。根据第六段中的“…cadets with strong internal and strong instrumental motives for attending West Point performed worse on every measure than did those with strong internal motives but weak instrumental ones”可知,拥有较高内部动机和较低功利性动机更有助于事业的成功。

阅读下面材料,回答问题。

在一节美术公开课上,教师在教学生画吃虫草。整个一节课,教师完全按照备课内容、时间安排,在课堂上用15分钟讲授吃虫草的特性,用10分钟让学生六个人一组,分组讨论“吃虫草为什么可以吃虫子”。然后教师在听取了两个组的讨论结果后,从自己的教案上把正确答案抄在黑板 上。最后,让学生根据正确的描述,10分钟之内画一棵吃虫草。而在下课后,发现有1/5的学生仍然在埋头画画,还有几个学生则根本没有动笔。课后,评课者的意见如下:“把美术课上成了生物课”“讨论流于形式,学生没有真正参与到讨论中来”“这节课没有融入感情,没有表现发现美、创造美的过程”。

根据此次新课程改革的理念,请用教育学相关原理对案例进行分析。你如果是这个美术教师,你会怎么上这节课?

以下是《十几减九》的教学片段,阅读并回答问题。

教师先让学生独立思考例题“12 — 9”的计算方法,然后展开师生对话,交流算法。 师:谁来介绍自己的方法,告诉大家你是怎么想的?

生1:我是数出来的。

师:你是怎么数出来的呢?

生1:我心里想着9,然后从9往下数(用手指表示),一直数到12,数了3个数,所以12减9就等于3。

师:你能给你的方法起个名称吗?

生1:(想了想)那就叫“数手指”法吧。

生2:老师,我不用数手指,而是用小棒来摆。

师:你是怎么摆的,又怎么算呢?

生2:我先摆出12根小棒,然后拿走9根,剩下3根,12减9就等于3,这种方法叫“摆小棒”法。

师:好一个“摆小棒”法,你真行!

生3:我不用数手指,也不用摆小棒就能算出来!

师:是吗?那就把你的高招说一说!

生3:(得意地)我把12分成10和2,先用10减9等于1,再用1和2加起来就等于3。

师:哇!你真聪明,能想出这么巧妙的方法,老师佩服你!那你给这种方法起名称了吗?

生3:我不知道该叫什么方法好。

师:还有谁的方法和生3的一样?你们一起来商量一下,给这种方法起个什么名称。

学生你一言我一语,说出了很多名称,有的叫“分开减”法,有的叫“先算10”法,有的说是“10 减”法,还有的叫“先算减,再算加”法。

师:这些名称都有道理,老师把你们的这些说法综合起来,起一个又简单又合理的名称,你们同意吗?

生:同意!

师:那就叫“破十法”吧!

生4:我还有一种方法比“破十法”还好!

师:是吗?怎么个好法,你说说!

生4:因为我知道9加3等于12,所以12减9就等于3,这种方法叫“想加算减”法!

师:你真会学习,能运用已经学过的知识来解决新问题。

生5:老师,我还有一种更好的方法,叫“连续减”法!

师:(惊讶地)真的吗?怎么连续减呢?

生5:(兴奋地跑上讲台)我先用12里的2减去9里面的2,再用10减去剩下的7就得到3。

师:你真是一个“小数学家”,太了不起了 !

试述此教学片段中,体现了教师与学生互动教学活动的哪些特点?

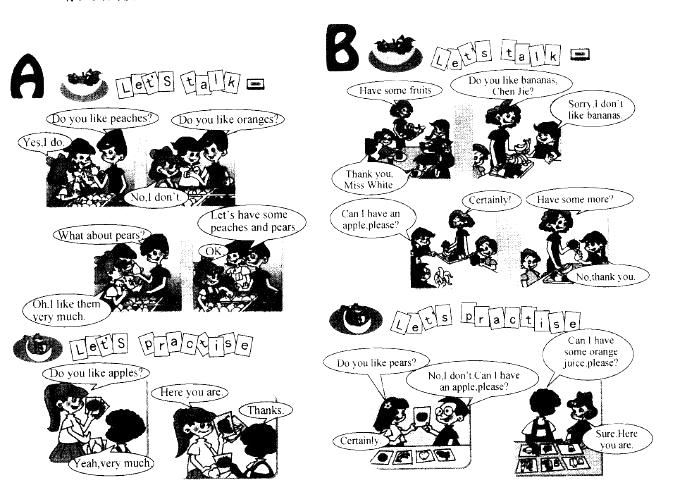

题目一:如指导中年段小学生学习上述内容,试拟定教学目标和教学重点。(15分)

题目二:根据拟定的教学目标和教学重点,设计课堂教学环节。(25分)

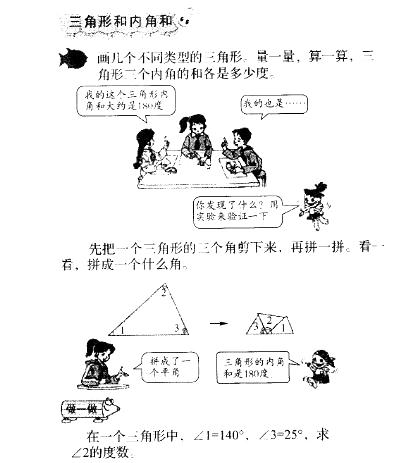

问题(一):如指导中年段小学生学习上述内容,试拟定教学目标和教学重点。(15分)

问题(二):根据拟定的教学目标和教学重点,设计课堂教学环节。(25分)

简述小学生想象力的特点。

简述布鲁纳的认知发现说及其对教学的启示。

简述教师运用谈话法时应注意的问题。

小学德育工作常用的奖惩属于( )法。

学生为了自己在班级中的成绩排名而努力学习,这样的学习动机主要属于( )。

—个人的思维活动能根据客观情况的变化而变化的思维品质称为思维的( )。